Warming sea surface temperatures in low-salinity oceans like the Baltic Sea is increasing cases of Vibrio bacteria infections

WHO: Craig Baker-Austin, Nick G. H. Taylor, Rachel Hartnell, Centre for Environment Fisheries and Aquaculture Science, Weymouth, Dorset, UK,

Joaquin A. Trinanes, Laboratory of Systems, Technological Research Institute, Universidad de Santiago de Compostela, Spain, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Environmental Satellite Data and Information Service, CoastWatch, Maryland, USA

Anja Siitonen, Bacteriology Unit, National Institute for Health and Welfare (THL), Helsinki, Finland

Jaime Martinez-Urtaza Instituto de Acuicultura, Universidad de Santiago de Compostela, Spain

WHAT: Establishing patterns between Vibrio bacteria infection outbreaks and climate change in the Baltic Sea to be able to predict future outbreaks.

WHEN: January 2013

WHERE: Nature Climate Change, Vol 3, January 2013

TITLE: Emerging Vibrio risk at high latitudes in response to ocean warming (subs. req)

Imagine that it’s a hot summer’s day in Northern Europe. The heat wave has lasted for more than three weeks now and you’re just dying to get into the ocean for a swim to cool off, except that you can’t, because there’s been a bacteria outbreak in the water and going swimming will make you sick.

It doesn’t sound like fun does it? But it’s happening increasingly in the Baltic Sea, and it looks like climate change is providing the exact conditions these bacteria love.

Vibrio is a type of bacteria that grows really well in warm (>15oC) low-salinity (<25 parts per trillion salt) water. The most common type in estuaries and other shallow water is Vibrio vulnificus, which is related to the same bacteria that causes cholera (Vibrio cholerae). Not a nice family, really.

When you swim in water that has Vibrio bacteria, it immediately gets excited (yes, I’m aware that bacteria don’t have feelings) about any cuts or wounds you have and infects them giving you symptoms like vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pains and blistering dermatitis. Well, that’s a way to really ruin your summer.

If you’re really unlucky or immuno-compromised, Vibrio will give you blistering skin lesions, septic shock (life threatening low blood pressure) and possibly kill you 25% of the time. It’s an efficient bacterium though, and will kill you in only 48hrs.

So why is Vibrio moving into the Baltic Sea more often? Climate change, combined with location.

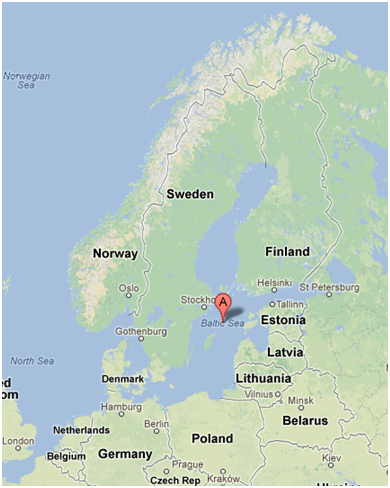

The Baltic Sea is the largest low-salinity marine ecosystem on Earth, and is surrounded by highly populated countries, meaning there are 30million people living within 50km of the shores of the sea. The Baltic Sea is also warming rapidly.

The researchers found that the sea surface temperature has been warming in excess of 1oC per decade, which is seven times the global average rate of warming. The rate is also increasing. From 1850 to 2010, the rate of warming was .51oC per century. The warming between 1900 to 2010 was at a rate of .77oC per century, and more recently the warming from 1980-2010 has been at a pace of 5oC per century, which is scarily fast for planetary systems.

Their data shows that for every 1oC increase in the summer maximum sea surface temperature, the rate of observed Vibrio infections increased by almost 2 times. This of course, gets compounded with the fact that increased summer maximum sea surface temperatures mean the air temperature is also hotter, and a hotter summer means more people head to the beach and get infected.

Even worse, recent research shows that some Vibrio bacteria’s ‘pathogenic competence’ (which is scientist for how good it is at infecting you) could be improved by increased temperatures.

Which all adds up to a nasty sequence of events where many more people than usual get nasty skin lesions. So what should we do about it? The researchers suggest monitoring conditions and sending out health advisories for when the sea surface temperatures are >19oC for three weeks or more as well as using predictive models to try and work out where/when the worst outbreaks might occur.

I don’t know about you, but nasty bacterial infections from a warmer ocean on a slowly cooking planet doesn’t sound like a good idea to me. So I’d also like to suggest we stop burning carbon so I and the people of Northern Europe can continue to swim in the summer.

Pingback: Don’t go in the Water | Amy Huva

Pingback: Don’t go in the Water | Amy Huva